[ad_1]

Survivalists, drifters, and divorcées across a resurgent wilderness

Drive far enough into Texas from the Louisiana border, and you’ll see the ground dry, the earth crumble into dust. Eventually, the photographer Bryan Schutmaat told me, the strip malls fade into the rearview mirror, the landscape opens, and the American West begins.

Schutmaat has long been fascinated by the West; as he toured with punk bands in his teens and early 20s, he felt himself drawn to the region and its open space. His new book, Sons of the Living, documents a decade’s worth of more recent journeys through the West and features the hitchhikers and “road dogs” he met along the way.

First in a Subaru Forester and then in a Toyota Tacoma pickup, Schutmaat would set out from his home in Austin and drive toward California. He’d weave from Interstate 10 onto the more isolated two-lane blacktop highways snaking into the remote reaches of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. When he sensed he was encroaching on the sprawl of Los Angeles, he’d turn around. All told, he spent more than 150 days on the road; many nights, he slept in his car.

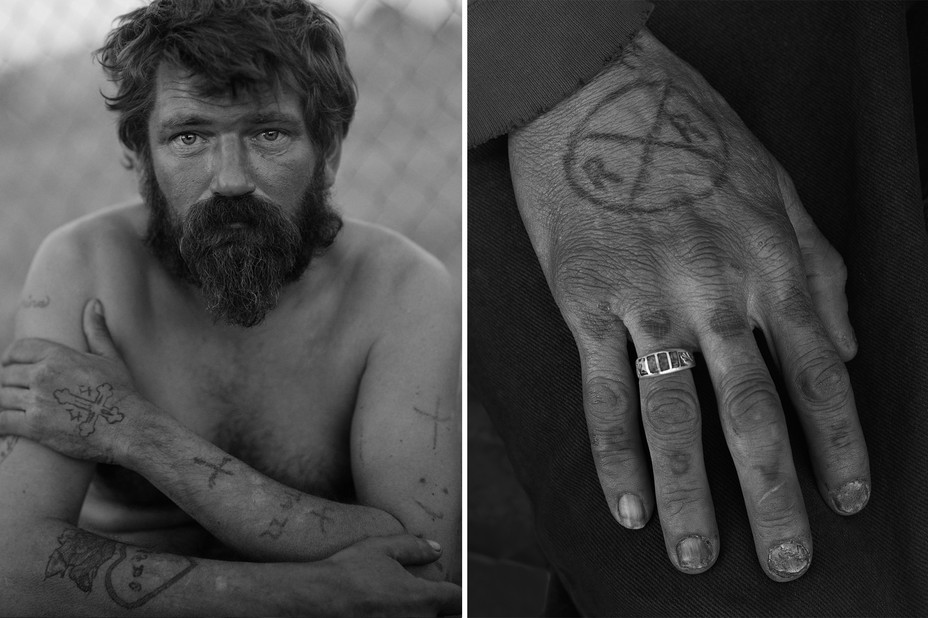

At truck stops and campgrounds, Schutmaat would shoot portraits of people he encountered and offer to ferry them from one place to the next. Behind the wheel or over a shared meal or beer, he’d listen as they told their stories: One man, Tazz, had taken to the road after he’d been released from prison and struggled to find work. He had drifted far from his childhood in Maine, and his thick Down East accent clashed with his surroundings. He claimed to have once played childhood pranks on Stephen King’s home; later, he told Schutmaat, he committed more serious transgressions. Schutmaat spent several hours talking in a New Mexico Denny’s with another man, Walker, a tall traveler with resplendent facial hair; Schutmaat took his portrait in the light of a gas-station pavilion, Walker’s beard swaying in the breeze.

Schutmaat’s work challenges a mythology of the West that has long maintained a hold on the American imagination. Frederick Jackson Turner theorized that the country’s democratic culture was forged from its pacification of the western frontier; the novelist Wallace Stegner called the region “a geography of hope.” But like the Depression-era photographers Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, Schutmaat complicates rosy views of the region and its promise. The newspaper editor Horace Greeley is said to have encouraged one of his charges to “Go west, young man, go west and grow up with the country.” Sons of the Living makes clear that the West contains no guaranteed redemption.

Instead, Schutmaat’s photographs reveal what happens when a country grows old and fractured, its citizens isolated. The travelers Schutmaat photographed—widowers and addicts, migrant workers and survivalists, drifters and divorcées—are resilient, but not exactly hopeful. In Schutmaat’s images of abandoned billboards and collapsing towns, there’s a feeling not of humanity taming the wilderness, but of the wilderness steadily reasserting itself over a crumbling human presence.

When Schutmaat was traveling, he’d pull over on the side of the road at nightfall and hike up the highway embankment. He’d set up his camera somewhere elevated and leave the shutter open for five, even 10 minutes. Through his lens, the sparse sets of headlights on the road below would melt into a river of light: the road erased, a wildness restored.

These photos appear in Bryan Schutmaat’s new book, Sons of the Living.

[ad_2]

Source_link